In the floating world where all things change

Love never changes by promising never to change.

(Geisha song)

During Edo-period Japan (1600-1867), the yujo were the highest class of all courtesans. These sex professionals were trained in the bedroom arts from the time they were young: blossoming into womanhood, mastering the erotic arts, flourishing as a prostitute of a high order. Prostitution during that era of Japan was legal, but carefully licensed. One such ‘red lantern district’ was Shimabara, the Pleasure Quarter of Kyoto. Another was Yoshiwara, the Pleasure District of Edo (Tokyo).

The yujo were not geisha. They were the royalty of prostitutes, the refined artisans of erotica and lovemaking. Seduction was their art form from the way they used their harigata (dildo) to how to pleasure a man (shakuhachi しゃくはち or fellatio). Yujo knew about aphrodisiacs and the exotic practice of kissing (seppun). The Yujo women were “love artists.”

This romantic era of Japan was called Ukiyo

(Japanese: 浮世 “Floating World”)

From the Wikipedia resource, this Renaissance period of art and pleasure described the Edo pleasure district as:

“Yoshiwara, the licensed red-light district of Edo (modern Tokyo), which was the site of many brothels, chashitsu tea houses, and kabuki theaters frequented by Japan’s growing middle class.

People involved in mizu shōbai (水商売) (“the water trade”) would include hōkan (comedians), kabuki (popular theatre of the time), dancers, dandies, rakes, tea-shop girls, Kanō (painters of the official school of painting), courtesans who resided in seirō (green houses) and geisha in their okiya houses.

The courtesans would consist of yujo (women of pleasure/prostitutes), kamuro (young female students), shinzō (senior female students), hashi-jōro (lower-ranking courtesans), kōshi-jōro (high-ranking courtesans just below tayū), tayū (high-ranking courtesans), oiran (“castle-topplers,” named that way for how quickly they could part a daimyō (lord) from his money), yarite (older chaperones for an oiran), and the yobidashi who replaced the tayū when they were priced out of the market.

In addition to courtesans, there were also geisha/geiko, maiko (apprentice geishas), otoko geisha (male geishas), danna (patrons of a geisha), and okasan (geisha teahouse managers). The lines between geisha and courtesans were sharply drawn, however – a geisha was never to be sexually involved with a customer, though there were exceptions.

The term “water trade” (mizu-shobai 水商売) is the “floating world” which is metaphor for floating, drinking, and impermanence. Sex was like water. Water was “yin” and feminine, and, conversely, a man’s sexual energy was “yang” energy. Sex during the Edo-period Ukiyo life was imbued with poetry, art, and dream-like desire. Longing and secrets, mystery and lust.

Waiting anxiously for you

Unable to sleep, but falling into a doze—

Are those words of love

Floating to my pillow,

Or is this too a dream…?

My eyes open and here is my tear-drenched sleeve.

Perhaps it was a sudden rain.

(Geisha song)

Geisha were not permitted to have sexual relations with the yujo’s customers. The term “Geisha” means “Artist” and the art of Geisha was entertainment— dance, shamisen playing, and flirtatious conversation. The yujo were the sexual artists, great lovers, and ladies of pleasure. They were elegant enchantresses of the pillow.

Within the shoji screened worlds of tea houses, brothels, and the theater, geisha and yujo were not the only women of pleasure. There were varying levels of class and status within their own floating worlds— the Shiro (white) Geisha that entertained and flirted, the Joro (whore) Geisha were the tawdry types, and the Machi (town) Geisha were former dancing girls (odoriko). Lower class prostitutes and amateur whores were illegally working the towns outside of pleasure districts.

Even further into darkness were the unmentioned girls and women that came into the world of prostitution without a choice. Girls sold into brothels, not the beautiful sort of life that the yujo and geisha led. The Yoshiwara district alone was home to about 1,750 women in the 18th century.

Geisha embody the extreme feminine allure in Japan, as opposed to the wife’s position in Japanese society. Geisha are witty and elicit fantasies; they intrigue and delight. The wife at home may appreciate the geisha’s art of entertaining her husband, relieving her of such matters. The wife ruled the domestic household and her husband’s finances, raised children, while the geisha entertained, flirted, and enchanted.

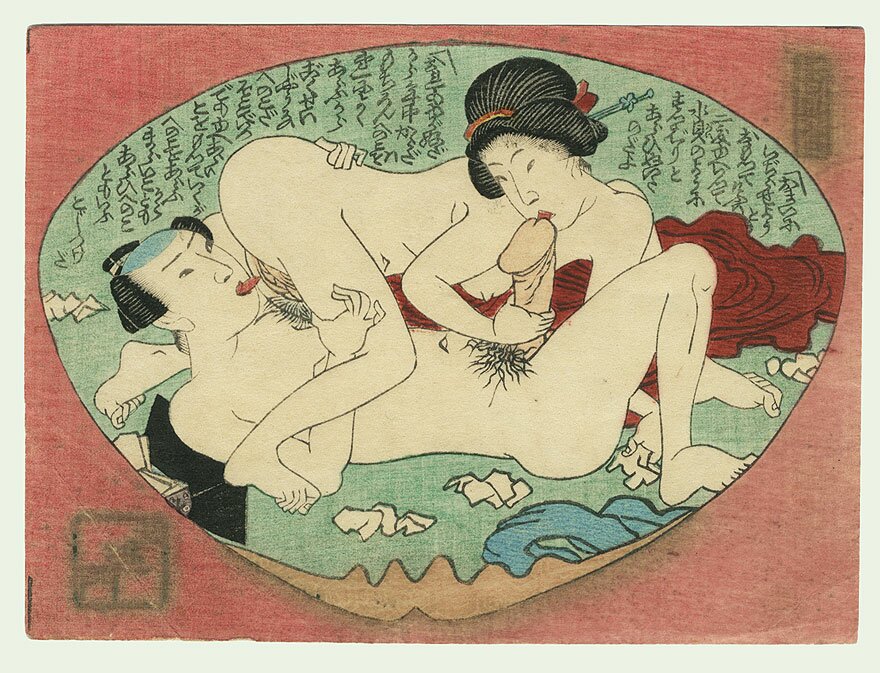

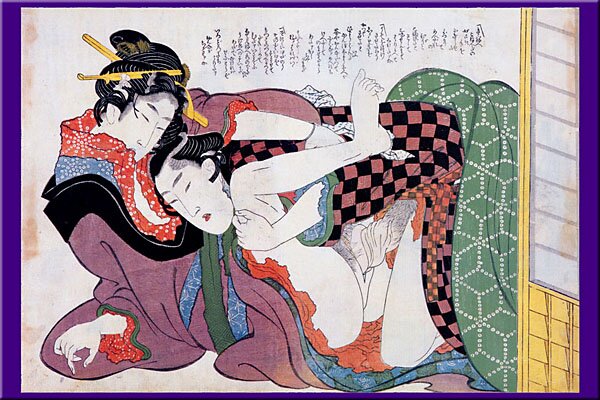

Shunga-e paintings were the erotica of the Edo-period, and the artists that created shunga-e were sometimes the same as those who made the famous Ukiyo-e woodblock prints— famous artists of Edo were also the creators of erotic prints and pornographic fantasies.

Artists of the Erotic Shunga-e were also great artists in general. Such as Katsushika Hokusai, who created Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (富嶽三十六景 Fugaku Sanjūrokkei) and the famous image The Great Wave off Kanagawa (神奈川沖浪裏 Kanagawa Oki Nami Ura).

Hokusai’s erotic art was also made with great talent. Most notably, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife

(蛸と海女 Tako to ama, Octopus and shell diver).

Making love with you

Is like drinking sea water.

The more I drink

The thirstier I become,

Until nothing can slake my thirst

But to drink the entire sea.

(Marichiko)

Romance and courtship in Heian-period Japan, pre-Edo times set in ancient Kyoto (Heian-kyo), painted the landscape for lovers brushing their hearts out in calligraphy into fervent love letters. Poetry was the vehicle of erotic love, longing, passion and desire. Lovemaking etiquette was such that even the ladies of the court and their noblemen were hot for sex and romance, writing poems to pursue, to enchant, and to express their innermost secrets of their hearts.

An excerpt from Lesley Downer’s book, Women of the Pleasure Quarters: The Secret History of Geisha:

“But what made Heian period most extraordinary was the way in which art and the cult of beauty were bound up with love. For more than sexual desire or gut-wrenching passion, love was an art form, an opportunity to put brush to paper, to immortalize the moment in a small literary gem.

Having heard that a certain lady was very beautiful or, even more titillating, had beautiful handwriting, a nobleman would sit down to compose a waka, a thirty-one syllable poem, and brush it, in his finest calligraphy, on delicately hued scented paper. When she received it, the lady would assess the handwriting and color of the paper as well as the wit and appropriateness of the poem before brushing a reply. The nobleman would be waiting with bated breath to see whether her handwriting and poem lived up to expectations.

If the exchange of poems was satisfactory, he would eventually assay a visit. He would creep in at night and immediately, in the pitch darkness, remove his clothes, lift the silken counterpane, lie down on the hard straw mat next to the lady and without further ado consummate the relationship. Slipping away before dawn, he would then brush an eloquent morning-after poem, bewailing the rising of the sun or the crowing of the cock announcing the hour of farewell. The lady in her turn would brush a reply. Thus through poems they communicated their decision as to whether to continue the affair or not.”

Erecting like

The upwards curve of a

Threatening shakuhachi

The shakuhachi is a flute, and ‘shakuhachi curve’ suggests a strong penis. The phallic symbol of the instrument allowed Edo-minded lovers to playfully muse about fellatio. As provocative as blowing a flute was to the lustful minds of Ukiyo era, the flute was used in many woodblocks prints to suggest the oral pleasure. Other slang terms for sex and sexual innuendos were “jade gate” for a woman’s sex and “jade stalk” and “matsutake” (or mushroom) for a man’s penis, and “selling spring” was to suggest selling sex, as the season “Spring” was utilized in poems and the sex trade as a multi-purpose term for sex.

I hold your head tight

Between my thighs and press

Against your mouth and

Float away forever in

An orchid boat

On the River of Heaven.

(Marichiko)

Geisha were not allowed by their very nature to fall in love. Neither were prostitutes. It was the danger of the heart that neither sort could manage. It would mean disaster for their very existence as temptresses. To pretend to love was one thing. To fall in love was another thing entirely. Flirtation and courting was full of sexual desire— the art of seduction was a play, an illusion. So then, what happens when the geisha or the prostitute falls in love?

Historically in such circumstances the geisha and prostitute were ruined, overcome by passion and desire, the longing too great for them to handle while luring and beguiling other men. Suddenly, the art of seduction she used for others is seemingly powerless, as her heart is unable to bear the games she once so artfully played, with her mind lost in reverie for her lover. She becomes overwhelmed by dreams of running away with her beloved. No longer can she play the seductress to the many men that pay her for her attentions. She is consumed by passion and caught in the great tidal pull of life’s mystery: Love.

Love me. At this moment we

Are the happiest

People in the world.

(Marichiko)

And her art and erotic craft is love. Like the saying “live by the sword, die by the sword,” the prostitute and geisha, artists of seduction and flirtation, are the femme fatales, the unattainable feminine, for which men would do anything for, and therefore the power they wield is turned upon them. Longing. Heartache. Waiting.

Night without end. Loneliness.

The wind has driven a maple leaf

Against the shoji. I wait, as in the

old days,

In our secret place, under the

full moon.

The last bell crickets sing.

I found your old love letters,

Full of poems you never published.

Did it matter?

They were only for me.

(Marichiko)

In this world

love has no color—

yet how deeply

my body

is stained by yours.

(Izumi Shikibu)

There are many stories about geisha and prostitutes falling in love with their customers that are married and cannot change their lives or young and impoverished men that cannot rescue them out of their bondage or position. In such cases, the solution was death. Like Romeo and Juliet, the lovers were doomed to tragedy. Kabuki plays such as Love Suicides at Sonezaki re-enacted the true story of a double suicide in 1703 by the great Japanese dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724) known as the “Shakespeare of Japan.” The story was about a beautiful courtesan Ohatsu that falls in love with handsome Tokubei, who is too poor to buy her out of her position as prostitute. He cannot follow through with his arranged marriage to another, due to his love for Ohatsu. His dowry already granted to him for his arranged marriage is then revoked by his uncle. The story continues and sorrow unfolds as the star-crossed lovers cannot be together.

Black hair

Tangled in a thousand strands

Tangled my hair and

Tangled my tangled memories

Of our long nights of lovemaking.

(Yosano Akiko)

But sometimes, when lovers meet, the erotic desire flames their very souls. Even as a customer pays for sex and affections, whether pretended or not, it enters a realm that is human. It can be a source of inspiration. The nature of sex is union, when two lovers are as one. Regardless of money and position, sex is the essence of life and the mystery of our being alive. If sex and flirtation and the realm of erotic are the prostitute’s trade, then the question is — what does the prostitute do when she herself falls in love? How can she continue being a lover to many men, when she only wants to belong to the one man she loves? Like any other, she feels it ravage her very soul— awakening her, making her feel alive, passionate, and creative. The heart has its own reasons and mysteries. But how can she give her body to other men for money (her livelihood) when her instinct is to be devoted to the one she loves?

Your tongue thrums and moves

Into me, and I become

Hollow and blaze with

Whirling light, like the inside

Of a vast expanding pearl.

(Marichiko)

”To fall in love is to play with fire,” Beautiful Eiko laughed. She had a tumbling mane of silky black hair, porcelain skin, and a mouth that tempted. She had many customers that adored her, dazzled her with gifts and exquisite kimonos. Then she met a man who had nothing but himself to give. He listened to her, understood her. For the first time in her life, she felt alive, inspired by love. But their love affair had to be secret. She was locked within the world of the prostitute’s life. This was unbearable for Eiko. When other men touched her, she felt only her lover’s hands. When other men embraced her, she longed for her lover only. When in the arms of her beloved, he became the only man in her world. She only wanted him, to belong to him, as her love was an all consuming passion, the very fire that awakened her soul and lit her aflame with desire.

No different, really—

a summer moth’s

visible burning

and this body,

transformed by love.

(Izumi Shikibu)

{References used for this article: Downer, Lesley, Women of the Pleasure Quarters: The Secret History of the Geisha, and Dalby, Liza, Geisha}

]]> https://eroticadujour.com/women-of-pleasure-the-floating-world-of-desire/feed/ 0

by Dorianne Laux (b. 1952)

She is about to come.

This time, they are sitting up, joined below the belly,

feet cupped like sleek hands praying

at the base of each other’s spines.

And when something lifts within her

toward a light she’s sure, once again,

she can’t bear, she opens her eyes

and sees his face turned away,

one arm behind him, hand splayed

palm down on the mattress, to brace himself

so he can lever his hips, touch

with the bright tip the innermost spot.

And she finds she can’t bear it—

not his beautiful neck, stretched and corded,

not his hair fallen to one side like beach grass,

not the curved wing of his ear, washed thin

with daylight, deep pink of the inner body—

What she can’t bear is that she can’t see his face,

not that she thinks this exactly— she is rocking

and breathing— it’s more her body’s thought,

opening, as it is, into its own sheer truth.

So that when her hand lifts of its own volition

and slaps him, twice on the chest,

on that pad of muscled flesh just above the nipple,

slaps him twice, fast, like a nursing child

trying to get a mother’s attention,

she’s startled by the sound,

though when he turns his face to hers—

which is what her body wants, his eyes

pulled open, as if she had bitten—

she does reach out and bite him, on the shoulder,

not hard, but with the power infants have

over those who have borne them, tied as they are

to the body, and so, tied to the pleasure,

the exquisite pain of this world.

And when she lifts her face he sees

where she’s gone, knows she can’t speak,

is traveling toward something essential,

toward the core of her need, so he simply

watches, steadily, with an animal calm

as she arches and screams, watches the face that,

if she could see it, she would never let him see.

*

Se Praj (17th century)

Your breasts will not fall.

Why clothe them with flowers?

Your folded arms are a wall,

love inviting me over.

*

]]> https://eroticadujour.com/erotic-poems-for-lovers/feed/ 1

“Spring quickly passes,

everything perishes.

I cry out loud

whenever your touches

tingle my breasts.”

Yosano Akiko

(1878-1942)

Yosano Akiko was a goddess of poetry. She was also an educator, a feminist, and an anti-war critic. I did not know until recently that she was also a mother.

Yosano Akiko had 13 children (11 children survived). She was pregnant for nearly a decade or more. The amount of laundry she must have had (hand washing, no washing machines back then). She had to hand wash all the cotton (sarashi) undergarments beneath her kimono, and, lest we forget… diapers. No local supermarket or CostCo in existence to buy a package of disposable diapers (though she’d probably enjoy buying in bulk) in her day. Still, with all the laundry, diapers and babies, nothing dampened her creative passion and erotic spirit. She was a formidable goddess of poetry. Hers was a life of passionate literature, many children, a love triangle, and much laundry.

“Press my breasts,

part the veil of mystery,

a flower blooms there,

crimson and fragrant.”

Yosano Akiko created. A “creatrix” in the supreme sense, she wrote a prolific amount of poems and letters, eventually eclipsing her mentor husband, Yosano Tekkan, in the art of writing. Her power as a poet was tremendous, and quite revolutionary for her time. She was birthing babies, caring for her children (with some help from relatives and hired nannies thankfully), involved in an intricate love triangle between her husband and her close friend, and writing a new style of Japanese Tanka poetry. She possessed a brilliant, erotic mind that flowed with passionate force. Her poetry expressed the restrained passions of an experienced, sexually liberated woman, even as a young girl.

It was a pivotal moment in her awakening desire when she met Yosano Tekkan (also named “Hiroshi”, his pen name “Tekkan”). He was first her mentor, and then became her ‘married lover’, as Tekkan was into a second marriage. He continued to love his second wife, never wavering from his devotion to her, regardless of divorce (The second wife’s father disapproved of Tekkan, and demanded they divorce). Soon after, Akiko and Tekkan married. Because of Akiko’s love for Tekkan, her expressions of sexual love evolved into intensely erotic writings.

Midaregami (Tangled Hair) was her first poetic collection of Tanka. 399 poems, among them, 385 are love poems about her desire for Tekkan, and also about her complex relationship with her close friend Yamakawa Tomiko (1879-1909). They were both involved in a love triangle with Tekkan. Akiko and Tomiko were both intertwined emotionally as close friends, both poets, and both in love with Tekkan. Tekkan maintained love relations with all his women, but Akiko demanded to be the queen bee.

“I whisper to you, “Stay in bed”

as I tenderly shake you awake

my dishevelled hair now

up in a Butterfly…

Kyoto morning!”

みだれ髪を京の島田にかへし朝ふしていませの君ゆりおこす

She was just twenty-two years old when Midaregami published, as an emerging poet. Akiko efficiently declared her love and sexual fire using “pillow words” such as “soft flesh” and “throbbing blood” to describe the emotions of sexual vitality and ripe eroticism.

For a woman in her time, late-Meiji era, her poems were full of potent juice, dripping with longing and passion. This was the new style of Tanka. The Tanka of the ‘Old School’ (Poetry Bureau School) faded, their style of tanka having been the most popular form of poetry after the New Meiji era began. The period of this style had been in existence for twelve hundred years in Japan. It was a style written in thirty-one syllables arranged in the 5-7-5-7-7 pattern. In 1887, Tanka poetry was changing with new voices, new expressions! For Akiko, she was a fresh voice, writing shockingly bold poetry that expressed pure sexual desire. In doing so, strong-willed Akiko defied her role as a conventional woman. This, in a sense, challenged the patriarchal system of Japan. Women of her day did not speak out about anything, especially of their blazing breasts and red flowers, suggestively illustrating their emotions and desires.

“Are you still longing,

seeking what is beautiful,

what is decent and true?

Here in my hand, this flower,

my love, is shockingly red.”

Following in the footsteps of the great female poets and writers of Japan before her, such as Lady Murasaki Shikibu (The Tale of Genji), Ono No Komachi, and Izumi Shikibu, namely, she did not adhere to social convention. Akiko illustrated women’s sexuality with words that described women’s desire as free, vibrant and independently their own. Women’s desire was raw and real, not passive, not waiting for men to seduce and court them. Akiko’s raw poetry caused a great sensation, and of course, great criticism.

“A thousand strands

of glistening deep black hair

in tangles, tangles,

all intertangled

like my dreams of you.”

Yosano Akiko was born in Sakai City in the Osaka Prefecture (Osaka). Her birth name was Shoko Ho. She changed her first name, as it carried the Chinese character, which could be used as either “Sho” and “Aki”, “ko” being the diminutive version given to girl’s names. She was the daughter of a merchant who loved art and literature, and owned a famous confectionary shop, Surugaya. Akiko’s mother was her father’s second wife. Akiko had two older step-sisters. She also had an elder brother, but he died young. Akiko’s father was very upset when his son died for many reasons. Of course, he mourned his son, but also, he was left with daughters. In Japanese families, sons, who inherit the family name, were very important. He was angry and rejected Akiko entirely, sending her away from their home. Akiko’s mother secretly visited Akiko, hiding her motherly love for her daughter. Eventually, feeling unloved by her parents, Akiko absorbed herself in books. She was secretive about reading books until late at night; stolen books from her father’s library. She read many Japanese classics, including The Tale of Genji by Lady Murasaki Shikibu (she was the equivalent of Shakespeare in Japanese literature). She also indulged in The Pillow Book, and Utsuho Monogatari, opening her erotic mind to the romantic world of love.

“Hair unbound, in this

hothouse of lovemaking.

Perfumed with lilies,

I dread the oncoming of

The pale rose of the end of night.”

She joined some literary circles and soon after, met Tekkan. Akiko admired Tekkan as a writer, and respected his work. Tekkan was the editor of a magazine, Myojo (Morning Star), in which Akiko contributed her writing. Her admiration for Tekkan started to grow into love. Tekkan had a wife and a child already, but this did not deter Akiko at all. Her passionate feelings for him were imminent, and describes the effect it had on her sexual awakening in one of her writings, titled “My Conception of Chastity”: “By an unexpected chance, I came to know a certain man and my sexual feelings underwent a violent change to a strange degree. For the first time I experienced the emotion of a real love that burned my body”

Real love that burned her body—– her statement echoed a poem by another femme fatale Japanese poetess, Ono no Komachi:

“You do not come

on this moonless night

I wake wanting you

my breasts heave and blaze

my heart burns up”

(Ono no Komachi)

And another version:

“I long for him most

during these long moonless nights

I lie awake, hot

the growing fires of passion

bursting, blazing in my heart.”

(Ono no Komachi)

Akiko eventually married Tekkan in 1902. Akiko and Tekkan continued their love affair, while things between the three of them (their involvement with Tomiko) became more complicated. Tekkan loved the two women. As part of an erotic triangle, many of Akiko’s poems expressed this ongoing affair, her tangled emotions, jealousy, and her friendship with Tomiko:

“I can give myself to her

in her dreams

whispering her own poems

in her ear as she sleeps beside me.”

And this one alluding to the threesome:

“Without a word

without a demand

a man and two women

bowed and parted company

on the sixth month.”

(This was written after Tomiko tragically died of tuberculosis)

“Pressing my breasts

I softly kick aside

the curtain of mystery

how deep the crimson

of the flower here.”

Breasts, lips, skin, shoulders, and hair described feminine sexuality.

In the poem, she touches her breasts, exploring sexual mystery for the first time, perhaps. Breaking all convention, she rips the clothes off of societal rules, and bares her body to the reader.

“Amidst the notes

of my koto is another

deep mysterious tone,

a sound that comes from

within my own breast.”

Before Japan’s New Meiji era, a woman’s beauty and sexuality were considered to be in the realm of courtesans and geisha. She rocked upon the pivotal point of her time like a cowgirl in the saddle, bareback and in full control of her horse. She did not seem to care about what people thought: she wrote out her passions without restraint.

Breasts tend to come up as one of her main symbols of expression. Breasts that represent feeding babies and motherhood, became sexual breasts of lovemaking and desire.

Akiko’s poetic line says it best: “my powerful breasts”

“Spring is short

what is there that has eternal life

I said and

made his hands seek out

my powerful breasts.”

Hair is another symbol of femininity and power. Long black hair has been admired as a symbol of great beauty for centuries in Japan. In the world’s history of art and literature, a woman’s hair is her “crowning glory” and her power, akin to the story of Samson and Delilah (and the destructive force of Medusa). It is part of women’s beauty, a graceful expression of identity in Japan.

In ancient court poetry of Japan, for instance, hair was used to show the inner complexities of women’s emotions. Izumi Shikibu, a female poet, 11th century:

“My black hair tangled

as my own tangled thoughts,

I lie here alone,

dreaming of one who has gone,

who stroked my hair till it shone.”

Tangled hair explains the confusions of her romantic heart. Its erotic description alludes to the sexual intimacy of lovers.

“A thousand lines

of black black hair

all tangles, tangles –

and tangles too

my thoughts of love!”

The flood of emotion and overwhelming feelings of love are expressed through hair.

As Akiko’s fame as a poet grew, she eventually gained power in her notoriety. She became the sole support of her family, leaving Tekkan to feel like a has-been and a good for nothing. He even wrote a poem, calling himself a “good for nothing”, fanning his own wife (the metaphor of being her servant, perhaps). Soon after, Akiko noticed her husband’s self-degrading misery. She suggested they move, which they did. They gave lectures together on The Tale of Genji. But soon they clashed on their interpretations of the classic epic “monogatari” (story-telling). They began to quarrel.

Akiko was overworked, having to support all their children by the income her writing produced. She was lecturing, writing, and putting up with her good for nothing, womanizing, has-been of a husband, and bringing home the bacon to take care of their 11 children. She considered divorce, another brave thing to do, but she knew that would drive the stake into Tekkan’s heart and ruin his life completely. She thought to suggest that they live separately, but that would create gossip, which would also harm Tekkan.

So she did a very sly thing—- she knew that Tekkan had always desired to live abroad. She raised enough money for Tekkan to travel to Europe. She wrote her poems on folding screens, selling them to create the funds. She received an advance from her books, and sent Tekkan to France in 1911. Tekkan felt as though he was being exiled for his “laziness” and so Akiko joined him in France for six months. They returned to Japan, never again to part.

She wrote of her complicated love and her desire to make it simple:

“Not speaking of the way

not thinking of what comes after,

not questioning name or fame,

here, loving love,

you and I look at each other.”

Yosano Akiko wrote about the emancipation of women and sexual freedom.

“Tangled Hair” Midaregami was her symbolic tour de force that well described her own complex life.

As a mother of three children, I greatly honor this majestic goddess of the pen. I have young children, I work full time as the sole support of my own family. I find at times my mind is tangled, and my life, complicated. Tangled by my own emotions regarding motherhood, motherly duties, responsibilities to my three young children, my sexual intensity and erotic desires, my longing, to write, to paint, to create—– all of these strands of long dark hair, in disarray. My own life as a woman in the modern day is complex. Marriages, ex-husbands, divorce, moving, always moving, where to belong, what to do for the children. Romantic feelings and erotic life take a back seat when life’s mundane issues become complicated, and daily demands call upon a mother. Just getting my two restless little girls to go to sleep so that I could finish this piece was a laborious task, irritating me as I could not attend to my own needs until they were tucked in and snoozing away. The multitude of feelings as a creative and artistic mother, like Akiko was, must have also complicated her life. As I sat in my girls’ room a while ago, I also soaked in their sweetness, marveled at the softness of their cheek as I caressed their faces, petting their silky heads, hair damp from the bath. As both of their breathing patterns regulated, I meditated on my good fortune as a mother. How lucky I was to have these beautiful, vibrant, healthy children. My oldest child, my son, sat in his room, reading a book. He enjoys his solitude and takes pleasure in reading. I realized that as frustrating as it was to put myself aside for the moment, sometimes the day, and sometimes an entire week— I felt that joy inside to be their mother.

I can only imagine, then, that Yosano Akiko was a loving mother, despite her creative force burning forth from her breasts. It is interesting to note that there isn’t much mention of her children and her life as a mother.

I would like to honor this glorious lady of the pen by writing this piece for a Mother’s Day post. As I read more about her life, I realized that her soul was crying out for love. She gave herself completely.

Also, the symbol of disheveled hair, Midaregami, is a multi-faceted metaphor: in Japan, women who had “tangled” or messy, uncombed hair were considered immoral, loose women. It evoked erotic freedom and perhaps made disheveled from an afternoon or evening of passionate lovemaking.

Lastly, I must mention the sexual energy it takes to create and birth just one child.

Akiko gave birth 13 times, lost two children, and raised 11 children, all while growing within her soul, a writing career.

The energy to manifest life— our “chi” is the purest source of sex. Erotic life of a woman also goes hand in hand with a woman’s sexual energy, her fertility. Her fertile mind, body and soul is made palpable by her desire. This erotic desire propelled her energy, her zest, and her sensual and sexual passions, blazing with the poetry and beauty of life itself.

“This autumn will end.

Nothing can last forever.

Fate controls our lives.

Fondle my living breasts

With your strong hands.”

]]> https://eroticadujour.com/awakening-the-love-goddess/feed/ 0