Desire. Longing. Lust.

Lust /ləst/ A noun that describes an intense sexual hunger for another. Middle English, from Old English, desire.

Lust is defined as “any source of pleasure or delight,” also “an appetite,” and “a liking for a person,” also “fertility” (of soil). Sense of “sinful sexual desire, degrading animal passion” (now the main meaning) developed in late Old English and in other Germanic languages, the derivative words mean “pleasure.”

I am fascinated by the erotic layers of desire, passion, and lust experienced in my own sex life. They are the spices of sex that go together just like cinnamon, nutmeg, and ginger in baking. As I love to cook and bake, I think of spices to explain lust, especially aphrodisiac spices. And when I think of lust, I think of moments I have desired someone beyond control. Moments so overwhelmed by lust, I become animal, lost in the heat of chemistry. Lust itself is the high note of sexual desire. It is the spark of what moves us from attraction to arousal and into action.

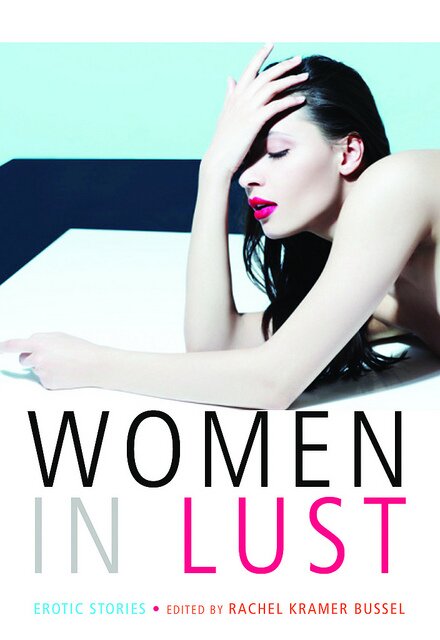

Reading other women’s stories about lust gives insight to the human response of sexual desire and passion. Erotica author and editor Rachel Kramer Bussel’s newest anthology Women in Lust is juicy and bursting with the passionate flavors of many voices. These stories taste as good as the musky inside of a lover’s thigh and the intoxicating mystery of an evolving kiss. Fresh and wonderfully compiled, twenty erotica authors combine their literary gifts and mix it all up into a lusty book.

I have read this book in bed. I have also read it in a cafe while having lunch, while having a pedicure, and I have taken moments to read it before meeting my lover for dinner. Erotica like this is inspirational, and musing on the subject of lust always whets my appetite for more. One of my most favorite stories from this anthology, Comfort Food by Donna George Storey, made me do a double take to the page, as the author’s voice reminded me uncannily of my own lustful fantasies (as well as a few realities) and my proclivity for combining food with lust. The featured dessert at the beginning of the story, a butterscotch pudding, was reminiscent of a recent sensual experience with my lover at a restaurant that served a butterscotch budino (an Italian pudding). Something about butterscotch pudding, I think. Its caramel flavor and satiny texture inspires lust for a taste of something just as creamy, just as delicious, if not more so. As the author describes, “Perhaps it was the creamy smoothness caressing my tongue like satin? Or the bottomless depth of flavor: caramel, tropical vanilla and an almost floral sweet cream, all mixed together with something else mysterious, alluring, even addictive? Whatever the reason for the magic, at that moment, I was very glad to be alive. When I finished my dessert, resisting the urge to lick the bowl clean, I waved over the pretty waitress.”

The story evolves from wanting the recipe to something more than a desire for ingredients from the chef.

Cherry Blossom by Kayar Silkenvoice is another story that capitvated me. The erotic tale takes place at a ryokan in Kyoto, Japan, where bathing in hot onsen waters and a massage transcends within the beautiful and sudden moment of desire. I loved the fluidity of Silkenvoice’s writing, as graceful as cherry blossoms falling upon hot spring water, illustrating the concentrated delicacy of sexual energy between two women for one another.

And lust can be so overpowering that we might feel like an animal, wanting to bite the one we desire because the feeling of lust is so strong. In Bite Me by Lucy Hughes, an exploration in pain, lust, and her lover’s request to bite him piques her curiosity and questions her indifference to this kind of fetish, pushing her beyond boundaries.

This book gives the reader a bouquet of delights, all clamoring with lust, displaying its words, paragraphs, and letters in sinuous sentences and wanton descriptives. As most of Rachel Kramer Bussel’s erotica anthologies are sexy, this one is hot off the press, and one to lust for. This delicious book would make anyone blush with lustful wonder.

Women in Lust is a sexy read. You can buy it online or visit the Women in Lust blog to discover more about the authors. I admire Rachel Kramer Bussel’s work as both an editor and author. Read about the Lusty Lady herself here on her main website.

The stories and their authors:

Naughty Thoughts by Portia Da Costa

Guess by Charlotte Stein

Her, Him, and Them by Aimee Pearl

Bayou by Clancy Nacht

Smoke by Elizabeth Coldwell

Bite Me by Lucy Hughes

Ride a Cowboy by Del Carmen

Queen of Sheba by Jen Cross

Hot for Teacher by Rachel Kramer Bussel

Unbidden by Brandy Fox

Something to Ruin by Amelia Thornton

Guitar Hero by Kin Fallon

Ode to a Masturbator by Aimee Herman

Orchid by Jacqueline Applebee

Cherry Blossom by Kayar Silkenvoice

Rain by Olivia Archer

The Hard Way by Justine Elyot

Strapped by K D Grace

Beneath My Skin by Shanna Germain

Comfort Food by Donna George Storey

“Tired of bein’ lonely, tired of bein’ blue,

I wished I had some good man, to tell my troubles to

Seem like the whole world’s wrong, since my man’s been gone

I need a little sugar in my bowl,

I need a little hot dog, on my roll

I can stand a bit of lovin’, oh so bad,

I feel so funny, I feel so sad”

~ “I NEED A LITTLE SUGAR IN MY BOWL” BESSIE SMITH 1931

Where to begin? This is a phenomenal read. The stories, personal essays, and confessions of sex, love, sexuality, and all that connect, by women, are real, timeless, and full of life. Real life.

This anthology of “Real Women Writing About Real Sex” is a treasure of experiences and stories by women. These women speak about their lives, They tell us about sex in all its many forms: marriage struggles, love and getting pregnant while abroad in Spain (“A Fucking Miracle” by Elisa Albert), stories about childhood sexuality: caught kissing and playing doctor in the closet (“Peekaboo I See You” by Anne Roiphe) and hilarious motherhood observations, parenting dilemmas, and marital-bed sex (“The Diddler” by J.A.K. Andres). There are internal contradictions, secret erotica publishings and prudish thoughts of a sex novelist (“Prude” by Jean Hanff Korelitz) and love discovered during one-night stands (“Sex With a Stranger” by Susan Cheever). Longing, first time sex, losing virginity, and a bottle of Cointreau (“My Best Friend’s Boyfriend” by Fay Weldon). Take a wild ride with hot sex (“Love Rollercoaster 1975″ by Susie Bright) and fall back into an ex-boyfriend’s arms for a one-night fling in a luxury hotel to indulge before a double mastectomy (“Everything Must Go” by Jennifer Weiner). There are so many touching, moving, and brilliant stories by a myriad of amazing women writers, telling their tales of sex and everything that goes with it. There is also, to our delight, a short, short story by Erica Jong titled “Kiss” about her encounter with “a kiss that moistened oceans, grew the universe, swirled through the cosmos.”

Erica Jong begins in her introduction: “Why are we so fascinated with sex? Probably because such intense feelings are involved—- above all, the loss of control. Anything that causes us to lose control intrigues and enthralls. So sex is both alluring and terrifying.”

Elegantly, poetically, Erica Jong introduces the book by exploring the subject of women writing about sex, her process in handling the emotions of contributors, and her observations on what has changed much, and what has changed little, in the realms of women writing about sex. She comes to a conclusion that “writing about sex turns out to be just writing about life.”

Erica Jong, the author: award-winning poet, novelist, and essayist best known for her eight bestselling novels, including the international bestseller Fear of Flying. She is also the author of seven award-winning collections of poetry.

Her contributors, all marvelous real voices of women writers, telling us about their experiences, ranging from fiction to non-fiction. A well-crafted crazy quilt of sexual patches, making up a whole of fabric, many colors and stories of sex. The innocent curiosity of childhood sexuality, losing virginity, sex and illness, pregnancy, urgency of lust, desire, the best sex, the worst sex,— all aspects, facets, and layers of sex and sexuality in the experiences of women.

“Sex is life— no more, no less. As many of these stories demonstrate, it is the life force.” Sex is about being human.

Contributors:

Karen Abbott, Elisa Albert, J.A.K. Andres, Susie Bright, Susan Cheever, Gail Collins, Rosemary Daniell, Eve Ensler, Molly Jong-Fast, Susan Kinsolving, Julie Klam, Jean Hanff Korelitz, Min Jin Lee, Ariel Levy, Margot Magowan, Marisa Acocella Marchetto, Daphne Merkin, Honor Moore, Meghan O’Rourke, Anne Roiphe, Linda Gray Sexton, Liz Smith, Jann Turner, Barbara Victor, Rebecca Walker, Jennifer Weiner, Fay Weldon, Jessica Winter, Erica Jong

**I have worked very hard to find all the links above, but cannot find J. A. K. Andres mentioned anywhere except for Erica Jong’s Sugar in my Bowl mention. Please authors: if you are linked (or unlinked) and need to update me, please contact me at [email protected] or twitter: @butterflydujour

{photo of Sovereign Syre by Angelo de la Fuente}

To begin this post, I bring you Sovereign Syre… a brainy beauty that I have come to discover while meandering the multitude of erotic art realms. Sovereign Syre is the stage name for this Goddess du Jour— tells us about her sultry self in her BIO:

Sans-Culotte/Sans-Papier. Louve/fillette. Sex-Object. The Dollface Killah. Co-Foundrix http://darlinghouse.net I produce & perform in explicit erotic content. I started in the industry in 2009 as a model for the alt.porn site God’s Girls.

Since I started in the industry, I’ve shot with George Pitts, Tony Stamolis, Kenn Lichtenwalter, Andrew Einhorn, Nathan Appel, Keith Major, Dave Dawson, Ken Penn, Corwin Prescott, Ellen Stagg, Holly Randall, Collin J. Rae and many others. I can be found on godsgirls.com, zivity.com, staggstreet.com, hollyrandall.com, latenightfeelings.com, and have been featured many times on fleshbot.com.

I’ve kept a blog of my adventures in and out of adult modeling, Sans Jupe. I was featured in the 2011 NYC Sex Blogger’s Calendar and my blog has been reviewed by Hustler in their July 2011 issue. Sans Jupe is slated for publication next year in an expanded version. I’ve been featured as a model and poet in Whore magazine and interviewed/featured in various others.

I am becoming intrigued by this Goddess of Alt Porn. She is a woman that has that feminine mystique, that mystery, even ‘sans jupe’. As Nora Charles (Myrna Loy) in the Thin Man put it, “A woman needs a little mystery,” and Sovereign Syre has that ‘ol’ black magic’ that puts you under a spell.

Anais Nin wrote about ‘eroticism and women’ (among other topics) in her book, “In Favor of the Sensitive Man and other Essays,” and I felt it important to quote a few passages from this insightful piece of women’s wisdom. Whenever I read Anais Nin’s writings, regardless of it being “erotica” per se, or a non-fiction “essay,” it demonstrates the timelessness of her thoughts, perceptions, ideas. I am always astounded by her ability to capture these thoughts and put them to the page. Anais speaks of women as a true feminist, breaking the old patriarchal concepts, letting in new light, fresh air, to the collective of female sexuality:

“Women through their confessions reveal a persistent repression. In the diary of George Sand we come upon this incident: Zola courted her and obtained a night of lovemaking. Because she revealed herself as completely unleashed sensually, he placed money on the night table when he left, implying that a passionate woman was a prostitute.

But if you persist in the study of women’s sensuality, you will find what lies at the end of all studies, that there are no generalizations, that there are many types of women as there are women themselves. One point established, that the erotic writings of men do not satisfy women, that it is time we write our own, that there is a difference in erotic needs, fantasies, and attitudes. Explicit barracks or clinical language is not exciting to most women. When Henry Miller’s first books came out, I predicted women would like them. I thought they would like the honest assertion of desire which was in danger of disappearing in a puritan culture. But they did not respond to the aggressive and brutal language. The Kama Sutra, which is an Indian compendium of erotic lore, stresses the need to approach women with sensitivity and romanticism, not to aim directly at physical possession, but to prepare her with romantic courtship. These customs, habits, mores, change from one culture to another and from one country to another. In the first diary by a woman (written in the year 900), the Tales of Genji by Lady Murasaki, the eroticism is extremely subtle, clothed in poetry, and focused on areas of the body which a Westerner rarely notices: the bare neck showing between the dark hair and the kimono.

There is a common agreement about only one thing,—- that woman’s erogenous zones are spread all over her body, that she is more sensitive to caresses, and that her sensuality is rarely as direct, as immediate as man’s. There is an atmosphere of vibrations which need to be awakened and have repercussions on the final arousal.”

Susie Bright recently put out a blazing memoir, Big Sex Little Death.

Fragments of stories weave in and out of my thoughts after reading Susie Bright’s memoir, Big Sex Little Death. Stories that Susie experienced, with guts, audacity, and sexual independence.

She begins with her family and by no means is she excusing them. They are necessary for her tale to be told. Beginning where she herself began, from the lives and union of two complicated people—- her parents. Perhaps the raw emotions and scars are still too palpable to fully express her feelings about her parents, but Susie does well in illustrating her childhood nonetheless.

Susie, “intellectually precocious but socially inappropriate,” wearing glasses and hand-sewn dresses, artfully explains her parents’ divorce that coincided with the deterioration of her mother’s mental state. Her mother, Elizabeth Halloran from Fargo, North Dakota, and the Halloran family, her mother’s Irish side of the family tree— they come, arms full of all the misgivings that bring her to where she is now. The darkness can create beauty, as the old-fashioned photographic process of a darkroom exhibits, how photo paper placed into developing fluid, magically transforms paper into details of captured light. Her prose of memories develops from the darkness, her childhood desires to be held and loved, but instead hurt in so many ways.

As difficult as it is to describe a relationship between mother and child, Susie is honest in her description of her mother. You can feel her unspoken words in between the lines. The pain, anger, and sense of abandonment, layered with the remnants of love, and the longing to be loved by the one person she came from, that gave her life. It is heartbreaking and messy. Gracefully, eloquently, she carries on, and discovers her strengths. With a valiant spirit and strong sense of power, she is a lotus rising from the dark mud.

Susie is a natural born rule breaker, a non-conformist, and a sexual revolutionary. Her words glimmer and spark through the pages, multi-colored, glittering. A firecracker, a wild thing. She is a cosmic kaleidoscope of a human being. Bi-sexual, lesbian, heterosexual, there is no box. There have been many who wanted to box her in, put her in a category. There is no category for Susie Bright. She is coloring outside the lines, she is messy finger painting, she is strong and delicate all at once, and she is beyond it all.

Her first menstrual cycle marked the beginning of her teen angst. She skipped school during lunchtime for a luxurious moment of solitude, reading, watching Petticoat Junction on TV, and ironing her grilled cheese sandwich on the ironing board, using it as a sandwich press. Suddenly, bleeding from her first menstruation, she figured out a tampon insertion before returning to class:

“I saw a blue box on the laundry hamper I hadn’t paid attention to before. Tampax. Yes! A new box. It had a paper diagram. Annette Laurence, who sat behind me in algebra, had said tampons would ruin your virginity. But I felt like ruining something. I slid the tampon into my vagina, and it was like folding a perfect paper crane. I felt nothing— in a good way— and the blood was no longer running down my leg. Now I just had to clean everything up. I was really late for class.”

When Susie (or ‘Susannah’ when she is in trouble) returns to class, she is sent to the school principal’s office:

“I walked into Dr. Shalka’s office like a mad bear. A mad menstruating bear with Germaine Greer on my tongue.

“This is not right,” I said, before he could motion me to sit down. “My period just started at noon, and I had to figure out the Tampax all by myself and I am never late and you can’t discriminate against me just because I am menstruating—“

I probably didn’t get that far, actually. I remember the look on his face when I said the “female” word. Was it period or the one that started with m? You would’ve thought I had sat on his face with my “vagina.” He flushed, his giant hands fluttered at his desk, and he coughed repeatedly into his cloth hankie.”

Thus begins the tale of Susie Bright.

I have much more to say about her memoir, but feel my words inadequate. I get the sense that I need to read this memoir again. No words can capture the essence better than “Sexual Freedom” to express the life path of Susie Bright. So many moments where society and people want to put her in a category. I won’t do that to her. I cannot, therefore, say enough about Susie, outside the lines, outside of paragraphs and sentences, where she exists, free and wild and wonderful and 100% herself.

]]> https://eroticadujour.com/dujour-goddess-du-jour-anais-nin-eroticism-women-writing-susie-bright/feed/ 0

I’m so excited about my mailbox today, because I’ve received a wonderful gift:

SUGAR IN MY BOWL : Real Women Write About Real Sex

I’ve opened the galley up like an excited child that cannot wait— tearing off the wrapper, ripping the taped areas off in my imagination, and delving into the electronic pages. Of course, I must admit that previous to this act of hurriedly scanning the writings of women in this new book, I was scolding my eleven year old son for reading on his laptop under his bed covers. Mommy says turn off the laptop now. It’s like telling your kids not to eat cookies, and then eating them while whisking the cookies away from their hands. Well. I know I’m guilty.

Yesterday, I received the most exciting notification in my Twitter account:

Erica Jong is now following you on Twitter! Really? Erica Jong?

My childhood memory suddenly flashed back to the visual of Jong’s book Fear of Flying which decorated our living room coffee table. I see the book in my mind’s eye, there. My prepubescent body, a young girl— and the book, Fear of Flying, on the coffee table where, on the corner, I used to press my pubic area on, to get that funny tingling feeling that felt so good. I pressed and leaned against the edge of that table, unaware that Fear of Flying was about a woman’s liberation, sex, and full of all the things my own life experience would come to know. Leaning on the edge of the table, staring at the cover of that book. It was stacked there, among other books. I hadn’t read Fear of Flying yet, because I was only seven or so. I had, however, flipped through The Joy of Sex and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, secretly. Can’t remember when exactly, but it was in that same living room, where Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying lay, imprinted in my childhood memory, in the sunny yellow-walled living room, on the coffee table. One day, when practicing piano, I noticed it had moved to the bookshelf. Then I noticed the book in various other places in our house; my mother’s nightstand by her bed, on her pool lounge next to her large tortoiseshell sunglasses, by the reading chair with her glass of chardonnay. A woman’s story. Like lingerie and lipstick, it carried within it, a deeper message to my soul— becoming a woman is more than the surface of a book cover, or lacy fabric, or a slick of color to the lips. It was another world that I was yet to know. Not even Rainier Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet or Kahlil Gibran’s poetry could assuage my longing to know the complexities of {a woman’s} life experience. No, it had to come from the mouths, from the hearts and souls of women writers. Instinctively I knew that as a young girl.

After lecturing my son about the importance of sleep and how reading an actual book in print was better for him than staring at a laptop screen, I shut his bedroom door and scrolled through this book, SUGAR IN MY BOWL, on my own laptop. There is so much rich, wonderful content, I don’t know where to start. Even though I have this galley, I will buy the book in print. I love handling books, the feel of the bound pages. Even the introduction by Erica Jong is marvelous. She begins:

“Why are we so fascinated with sex? Probably because such intense feelings are involved—- above all, the loss of control. Anything that causes us to lose control intrigues and enthralls. So sex is both alluring and terrifying.”

Elegantly, poetically, Erica Jong introduces the book by exploring the subject of women writing about sex, her process in handling the emotions of contributors, and her observations on what has changed much, and what has changed little, in the realms of women writing about sex. She comes to a conclusion that “writing about sex turns out to be just writing about life.”

Her contributors, all marvelous real voices of women writers, telling us about their experiences, ranging from fiction to non-fiction. A well-crafted crazy quilt of sexual patches, making up a whole of fabric, many colors and stories of sex. The innocent curiosity of childhood sexuality, losing virginity, sex and illness, pregnancy, urgency of lust, desire, the best sex, the worst sex,— all aspects, facets, and layers of sex and sexuality in the experiences of women.

I cannot wait to read everything. “Sex is life— no more, no less. As many of these stories demonstrate, it is the life force.” Sex is about being human.

SUGAR IN MY BOWL

AUTHOR:

EDITED by ERICA JONG , With Contributions from: KAREN ABBOTT, SUSIE BRIGHT, HONOR MOORE, ELISA ALBERT, SUSAN CHEEVER, GAIL COLLINS, EVE ENSLER, JULIE KLAM, ARIEL LEVY, DAPHNE MERKIN, MEGHAN O’ROURKE, ANNE ROIPHE, LIZ SMITH, REBECCA WALKER, JENNIFER WEINER, FAY WELDON, JESSICA WINTER, MOLLY JONG-FAST, JEAN HANFF KORELITZ,LINDA GRAY SEXTON, ROSEMARY DANIELL, J.A.K. ANDRES, JANN TURNER, BARBARA VICTOR, MARISA ACOCELLA MARCHETTO, SUSAN KINSOLVING, MIN JIN LEE, MARGOT MAGOWAN & ERICA JONG

PUBLISHER: ECCO/Harper Collins

DATE OF RELEASE: June 14, 2011

]]> https://eroticadujour.com/ive-got-a-little-sugar-in-my-bowl/feed/ 0

“Spring quickly passes,

everything perishes.

I cry out loud

whenever your touches

tingle my breasts.”

Yosano Akiko

(1878-1942)

Yosano Akiko was a goddess of poetry. She was also an educator, a feminist, and an anti-war critic. I did not know until recently that she was also a mother.

Yosano Akiko had 13 children (11 children survived). She was pregnant for nearly a decade or more. The amount of laundry she must have had (hand washing, no washing machines back then). She had to hand wash all the cotton (sarashi) undergarments beneath her kimono, and, lest we forget… diapers. No local supermarket or CostCo in existence to buy a package of disposable diapers (though she’d probably enjoy buying in bulk) in her day. Still, with all the laundry, diapers and babies, nothing dampened her creative passion and erotic spirit. She was a formidable goddess of poetry. Hers was a life of passionate literature, many children, a love triangle, and much laundry.

“Press my breasts,

part the veil of mystery,

a flower blooms there,

crimson and fragrant.”

Yosano Akiko created. A “creatrix” in the supreme sense, she wrote a prolific amount of poems and letters, eventually eclipsing her mentor husband, Yosano Tekkan, in the art of writing. Her power as a poet was tremendous, and quite revolutionary for her time. She was birthing babies, caring for her children (with some help from relatives and hired nannies thankfully), involved in an intricate love triangle between her husband and her close friend, and writing a new style of Japanese Tanka poetry. She possessed a brilliant, erotic mind that flowed with passionate force. Her poetry expressed the restrained passions of an experienced, sexually liberated woman, even as a young girl.

It was a pivotal moment in her awakening desire when she met Yosano Tekkan (also named “Hiroshi”, his pen name “Tekkan”). He was first her mentor, and then became her ‘married lover’, as Tekkan was into a second marriage. He continued to love his second wife, never wavering from his devotion to her, regardless of divorce (The second wife’s father disapproved of Tekkan, and demanded they divorce). Soon after, Akiko and Tekkan married. Because of Akiko’s love for Tekkan, her expressions of sexual love evolved into intensely erotic writings.

Midaregami (Tangled Hair) was her first poetic collection of Tanka. 399 poems, among them, 385 are love poems about her desire for Tekkan, and also about her complex relationship with her close friend Yamakawa Tomiko (1879-1909). They were both involved in a love triangle with Tekkan. Akiko and Tomiko were both intertwined emotionally as close friends, both poets, and both in love with Tekkan. Tekkan maintained love relations with all his women, but Akiko demanded to be the queen bee.

“I whisper to you, “Stay in bed”

as I tenderly shake you awake

my dishevelled hair now

up in a Butterfly…

Kyoto morning!”

みだれ髪を京の島田にかへし朝ふしていませの君ゆりおこす

She was just twenty-two years old when Midaregami published, as an emerging poet. Akiko efficiently declared her love and sexual fire using “pillow words” such as “soft flesh” and “throbbing blood” to describe the emotions of sexual vitality and ripe eroticism.

For a woman in her time, late-Meiji era, her poems were full of potent juice, dripping with longing and passion. This was the new style of Tanka. The Tanka of the ‘Old School’ (Poetry Bureau School) faded, their style of tanka having been the most popular form of poetry after the New Meiji era began. The period of this style had been in existence for twelve hundred years in Japan. It was a style written in thirty-one syllables arranged in the 5-7-5-7-7 pattern. In 1887, Tanka poetry was changing with new voices, new expressions! For Akiko, she was a fresh voice, writing shockingly bold poetry that expressed pure sexual desire. In doing so, strong-willed Akiko defied her role as a conventional woman. This, in a sense, challenged the patriarchal system of Japan. Women of her day did not speak out about anything, especially of their blazing breasts and red flowers, suggestively illustrating their emotions and desires.

“Are you still longing,

seeking what is beautiful,

what is decent and true?

Here in my hand, this flower,

my love, is shockingly red.”

Following in the footsteps of the great female poets and writers of Japan before her, such as Lady Murasaki Shikibu (The Tale of Genji), Ono No Komachi, and Izumi Shikibu, namely, she did not adhere to social convention. Akiko illustrated women’s sexuality with words that described women’s desire as free, vibrant and independently their own. Women’s desire was raw and real, not passive, not waiting for men to seduce and court them. Akiko’s raw poetry caused a great sensation, and of course, great criticism.

“A thousand strands

of glistening deep black hair

in tangles, tangles,

all intertangled

like my dreams of you.”

Yosano Akiko was born in Sakai City in the Osaka Prefecture (Osaka). Her birth name was Shoko Ho. She changed her first name, as it carried the Chinese character, which could be used as either “Sho” and “Aki”, “ko” being the diminutive version given to girl’s names. She was the daughter of a merchant who loved art and literature, and owned a famous confectionary shop, Surugaya. Akiko’s mother was her father’s second wife. Akiko had two older step-sisters. She also had an elder brother, but he died young. Akiko’s father was very upset when his son died for many reasons. Of course, he mourned his son, but also, he was left with daughters. In Japanese families, sons, who inherit the family name, were very important. He was angry and rejected Akiko entirely, sending her away from their home. Akiko’s mother secretly visited Akiko, hiding her motherly love for her daughter. Eventually, feeling unloved by her parents, Akiko absorbed herself in books. She was secretive about reading books until late at night; stolen books from her father’s library. She read many Japanese classics, including The Tale of Genji by Lady Murasaki Shikibu (she was the equivalent of Shakespeare in Japanese literature). She also indulged in The Pillow Book, and Utsuho Monogatari, opening her erotic mind to the romantic world of love.

“Hair unbound, in this

hothouse of lovemaking.

Perfumed with lilies,

I dread the oncoming of

The pale rose of the end of night.”

She joined some literary circles and soon after, met Tekkan. Akiko admired Tekkan as a writer, and respected his work. Tekkan was the editor of a magazine, Myojo (Morning Star), in which Akiko contributed her writing. Her admiration for Tekkan started to grow into love. Tekkan had a wife and a child already, but this did not deter Akiko at all. Her passionate feelings for him were imminent, and describes the effect it had on her sexual awakening in one of her writings, titled “My Conception of Chastity”: “By an unexpected chance, I came to know a certain man and my sexual feelings underwent a violent change to a strange degree. For the first time I experienced the emotion of a real love that burned my body”

Real love that burned her body—– her statement echoed a poem by another femme fatale Japanese poetess, Ono no Komachi:

“You do not come

on this moonless night

I wake wanting you

my breasts heave and blaze

my heart burns up”

(Ono no Komachi)

And another version:

“I long for him most

during these long moonless nights

I lie awake, hot

the growing fires of passion

bursting, blazing in my heart.”

(Ono no Komachi)

Akiko eventually married Tekkan in 1902. Akiko and Tekkan continued their love affair, while things between the three of them (their involvement with Tomiko) became more complicated. Tekkan loved the two women. As part of an erotic triangle, many of Akiko’s poems expressed this ongoing affair, her tangled emotions, jealousy, and her friendship with Tomiko:

“I can give myself to her

in her dreams

whispering her own poems

in her ear as she sleeps beside me.”

And this one alluding to the threesome:

“Without a word

without a demand

a man and two women

bowed and parted company

on the sixth month.”

(This was written after Tomiko tragically died of tuberculosis)

“Pressing my breasts

I softly kick aside

the curtain of mystery

how deep the crimson

of the flower here.”

Breasts, lips, skin, shoulders, and hair described feminine sexuality.

In the poem, she touches her breasts, exploring sexual mystery for the first time, perhaps. Breaking all convention, she rips the clothes off of societal rules, and bares her body to the reader.

“Amidst the notes

of my koto is another

deep mysterious tone,

a sound that comes from

within my own breast.”

Before Japan’s New Meiji era, a woman’s beauty and sexuality were considered to be in the realm of courtesans and geisha. She rocked upon the pivotal point of her time like a cowgirl in the saddle, bareback and in full control of her horse. She did not seem to care about what people thought: she wrote out her passions without restraint.

Breasts tend to come up as one of her main symbols of expression. Breasts that represent feeding babies and motherhood, became sexual breasts of lovemaking and desire.

Akiko’s poetic line says it best: “my powerful breasts”

“Spring is short

what is there that has eternal life

I said and

made his hands seek out

my powerful breasts.”

Hair is another symbol of femininity and power. Long black hair has been admired as a symbol of great beauty for centuries in Japan. In the world’s history of art and literature, a woman’s hair is her “crowning glory” and her power, akin to the story of Samson and Delilah (and the destructive force of Medusa). It is part of women’s beauty, a graceful expression of identity in Japan.

In ancient court poetry of Japan, for instance, hair was used to show the inner complexities of women’s emotions. Izumi Shikibu, a female poet, 11th century:

“My black hair tangled

as my own tangled thoughts,

I lie here alone,

dreaming of one who has gone,

who stroked my hair till it shone.”

Tangled hair explains the confusions of her romantic heart. Its erotic description alludes to the sexual intimacy of lovers.

“A thousand lines

of black black hair

all tangles, tangles –

and tangles too

my thoughts of love!”

The flood of emotion and overwhelming feelings of love are expressed through hair.

As Akiko’s fame as a poet grew, she eventually gained power in her notoriety. She became the sole support of her family, leaving Tekkan to feel like a has-been and a good for nothing. He even wrote a poem, calling himself a “good for nothing”, fanning his own wife (the metaphor of being her servant, perhaps). Soon after, Akiko noticed her husband’s self-degrading misery. She suggested they move, which they did. They gave lectures together on The Tale of Genji. But soon they clashed on their interpretations of the classic epic “monogatari” (story-telling). They began to quarrel.

Akiko was overworked, having to support all their children by the income her writing produced. She was lecturing, writing, and putting up with her good for nothing, womanizing, has-been of a husband, and bringing home the bacon to take care of their 11 children. She considered divorce, another brave thing to do, but she knew that would drive the stake into Tekkan’s heart and ruin his life completely. She thought to suggest that they live separately, but that would create gossip, which would also harm Tekkan.

So she did a very sly thing—- she knew that Tekkan had always desired to live abroad. She raised enough money for Tekkan to travel to Europe. She wrote her poems on folding screens, selling them to create the funds. She received an advance from her books, and sent Tekkan to France in 1911. Tekkan felt as though he was being exiled for his “laziness” and so Akiko joined him in France for six months. They returned to Japan, never again to part.

She wrote of her complicated love and her desire to make it simple:

“Not speaking of the way

not thinking of what comes after,

not questioning name or fame,

here, loving love,

you and I look at each other.”

Yosano Akiko wrote about the emancipation of women and sexual freedom.

“Tangled Hair” Midaregami was her symbolic tour de force that well described her own complex life.

As a mother of three children, I greatly honor this majestic goddess of the pen. I have young children, I work full time as the sole support of my own family. I find at times my mind is tangled, and my life, complicated. Tangled by my own emotions regarding motherhood, motherly duties, responsibilities to my three young children, my sexual intensity and erotic desires, my longing, to write, to paint, to create—– all of these strands of long dark hair, in disarray. My own life as a woman in the modern day is complex. Marriages, ex-husbands, divorce, moving, always moving, where to belong, what to do for the children. Romantic feelings and erotic life take a back seat when life’s mundane issues become complicated, and daily demands call upon a mother. Just getting my two restless little girls to go to sleep so that I could finish this piece was a laborious task, irritating me as I could not attend to my own needs until they were tucked in and snoozing away. The multitude of feelings as a creative and artistic mother, like Akiko was, must have also complicated her life. As I sat in my girls’ room a while ago, I also soaked in their sweetness, marveled at the softness of their cheek as I caressed their faces, petting their silky heads, hair damp from the bath. As both of their breathing patterns regulated, I meditated on my good fortune as a mother. How lucky I was to have these beautiful, vibrant, healthy children. My oldest child, my son, sat in his room, reading a book. He enjoys his solitude and takes pleasure in reading. I realized that as frustrating as it was to put myself aside for the moment, sometimes the day, and sometimes an entire week— I felt that joy inside to be their mother.

I can only imagine, then, that Yosano Akiko was a loving mother, despite her creative force burning forth from her breasts. It is interesting to note that there isn’t much mention of her children and her life as a mother.

I would like to honor this glorious lady of the pen by writing this piece for a Mother’s Day post. As I read more about her life, I realized that her soul was crying out for love. She gave herself completely.

Also, the symbol of disheveled hair, Midaregami, is a multi-faceted metaphor: in Japan, women who had “tangled” or messy, uncombed hair were considered immoral, loose women. It evoked erotic freedom and perhaps made disheveled from an afternoon or evening of passionate lovemaking.

Lastly, I must mention the sexual energy it takes to create and birth just one child.

Akiko gave birth 13 times, lost two children, and raised 11 children, all while growing within her soul, a writing career.

The energy to manifest life— our “chi” is the purest source of sex. Erotic life of a woman also goes hand in hand with a woman’s sexual energy, her fertility. Her fertile mind, body and soul is made palpable by her desire. This erotic desire propelled her energy, her zest, and her sensual and sexual passions, blazing with the poetry and beauty of life itself.

“This autumn will end.

Nothing can last forever.

Fate controls our lives.

Fondle my living breasts

With your strong hands.”

]]> https://eroticadujour.com/awakening-the-love-goddess/feed/ 0